Leaving Jesus

So I get on my iCalendar to do some scheduling for Easter week, and there’s no Easter. April Fool’s Day is there, which falls on the same day, but no Easter, no Good Friday. I read later that Apple has intentionally removed Good Friday and Easter from their calendar?

Hard to know for sure as internet information goes these days. But that I wouldn’t have been particularly surprised if it were true spoke volumes about what seems to be more and more sure—that we have entered a post Christian culture in the US.

Millions have been leaving mainline Protestant denominations for decades, but over the past ten years, a million have also left the Baptist Convention and even Evangelicals have lost up to ten percent of their membership. Various studies show that over 60 percent of young people don’t identify as Christian, and a group called the “nones,” those who refuse any religious identification, has grown to over a quarter of the population.

One Baptist leader is quoted as saying that there’s “no longer a social benefit to identifying as a Christian…often not only no social prestige to gain, there’s also prestige to lose if you say you are a Christian in our society.”

If that’s true, Christianity is coming full circle. From an oppressed minority in the first century, Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire by the fifth century and from there the state religion of Europe, which exported it starting in the fifteenth century with the oppression of most of the indigenous world during the Colonial period. By the twentieth century, even as European empires disintegrated, Christianity remained a social institution in the West, inseparably linked with white privilege. But now in the early twenty first century, white Christians have become a minority in the US, and in the minds of some in the majority, legitimate targets for marginalization.

But regardless of the sins of the church and its people, what about Jesus? It’s beyond irony that Jesus, a man of color who championed the marginalized of his day, is identified with Western Christianity, which has come to be identified with the oppression of the Colonial period and the exclusionary and scientifically implausible beliefs of some churches. For many socially and scientifically conscious people, leaving Jesus has become almost an imperative as they try to balance their ethics, spirituality, and common sense.

Do we have to leave Jesus to be inclusive? To be scientifically relevant? Socially tolerant? To be able to hang on to our common sense and rational thought while still pursuing an authentic spirituality?

Some twenty five years ago, I hit that crossroads. After growing up in the Catholic church and a short time in a religious order out of high school, I found myself back in church some fifteen years later in an Evangelical setting. I was already in leadership and pastoral training when the full implications of the doctrine and practice I was studying and living forced me to question whether I could faithfully continue as a Christian and follower of Jesus. But I loved my church community and friends, and I needed to see if there was anything I’d missed, anything anywhere that could rehabilitate Jesus and church and keep me home.

I began studying Christian origins, which led to the Hebrew roots of Christianity, which led to the native language Jesus spoke…which led me to an ancient, Eastern Jesus I’d never met before. There in those silent pages and in my heart of hearts—stripped of as much of twenty centuries of politics, dogmatic imperatives, and cultural and linguistic misunderstanding as my mind would allow—stood a Jesus who spoke with a clarity and ground-zero wisdom, a common sense and radical compassion, a constant pointing beyond himself to a love so fierce it demanded inclusion, because it literally was inclusion itself to all who wanted to be included.

I had to be willing to let go of what I had always been taught before I could see anything other, but life had already done much of that painful work for me. I was willing, though not yet entirely ready. That came later. It is endlessly ironic to me that at the moment I became entirely ready to leave Jesus, I also became entirely ready to see and follow him for the first time.

Maybe as a culture, we’re all getting to the same point. Maybe we have to exhaust our denominations and belief systems before we become entirely ready to return to what was once true about them.

But will we return? Or will we become so resentful in the exhausting, so convinced of some new certainty in place of the certainty we’re leaving that we remain equally closed to the risk of the truly radical? And if we do emerge blinking and staggering out of our exhaustion and certitude, will there be anyone there ahead of us, prepared to point in a different direction?

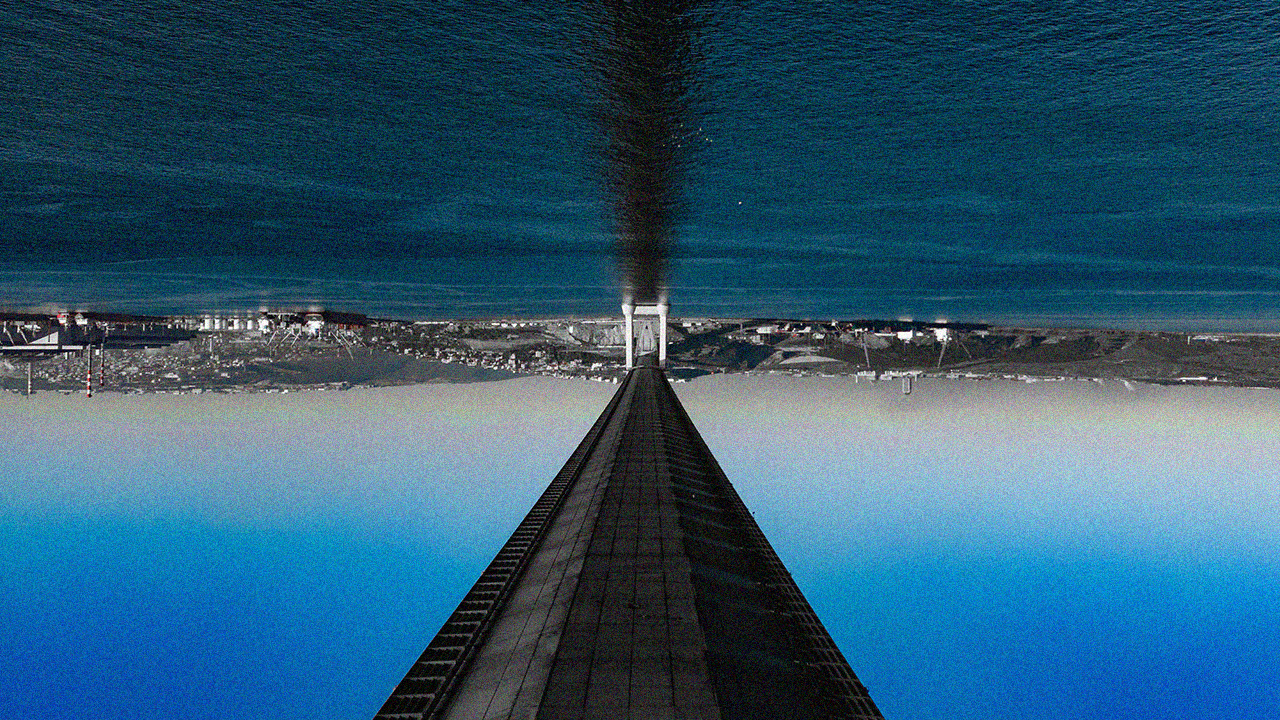

In a chaotic, postmodern culture that is freefalling toward complete detachment from its ancient spirituality, a longing for renewed inner experience is growing. And just as I did, more and more of us are coming to the conclusion that we need to leave Jesus in order to pursue an authentic spiritual journey. Been there, done that: we see Jesus as inextricably tied to an archaic, even superstitious system that has no power to take us anywhere we haven’t already been. But we haven’t been playing fair. We have remodeled and reshaped Jesus over centuries to fit Western culture, only to leave him now when he fails to deliver us out that culture’s grasp.

We will never need to leave Jesus to find authentic spirituality. We do need to become entirely ready to leave the Jesus we think we know, but that’s not the same thing. Any authentic spiritual journey will always recognize the voice of the authentic, Hebrew Jesus, a voice we can hear only if we accept Jesus’ original challenge to sell everything first, let go of what we think we know in favor of what really is.

Let’s all leave the Jesus of our own making and misunderstanding with enough of an open mind and desire for truth that we’re able to return to him when the journey bends and leads back home.